Editor’s Note: This recording starts shortly after Pir Vilayat began his lecture — we have preserved the starting sentence fragments for archiving purposes.

…A very deep study of Sufism, and also really partaking of the essence of Sufism, or the nourishment of Sufism. Of course, one can ask oneself well, who’s interested in Sufism, or who’s interested in an “ism?” And I can say the only reason why I’m interested in Sufism is not because I was born in the Sufi tradition, but because the outlook that has emerged from my discovery of Sufism has been absolutely traumatic in molding my whole way of thinking, for the reason that in my youth I was always seeking for the hermits in the Himalayas. Somewhat it’s in my blood, of course. And I was uplifted by their presence, by their being. And then somehow I had difficulty in relating that with fulfilling one’s purpose in life. And so I was see-sawing a lot from a retreat situation to back into life again. And I used to say that one should be able to bring the ascetic attunement in the middle of life.

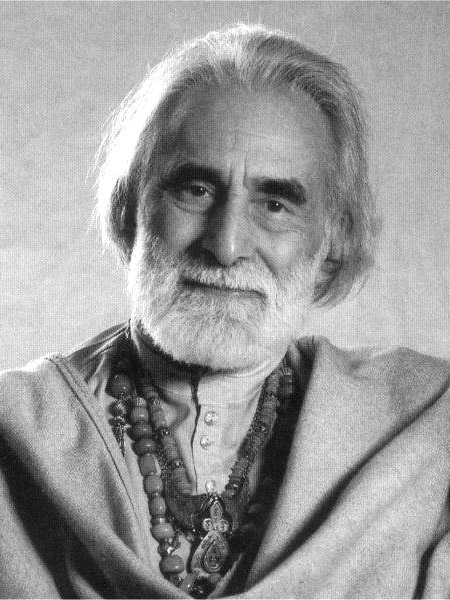

But I saw that it didn’t really happen like was in my mind. But there was something missing and what was missing was, that in fact there is quite the opposite outlook. Instead of reaching beyond one’s self, as I said this morning, there’s … as I said this morning, there’s meditation … meditating upwards and meditating downwards. And Sufism is of course meditating downwards–I may be overgeneralizing. And you see that in some of the photos of Murshid. He is bringing the heavenly spheres down in his being and grounding it, and existentiating it, actuating it, manifesting it.

So, what I would like to do is present rather the Sufis rather than Sufism. Now both of … I have difficulty in both words like, for example, Sufism is an “ism” and it’s the “ism” part that’s the least appealing to me. And that applies to any “ism.” And the other is the word, being a Sufi or not being a Sufi. That’s one thing that I always … that worries me a little bit or embarrasses me when somebody says, “Are you Sufi?” or “I’m a Sufi.” A label, and if there’s anything that is without label it is Sufism. So we’re attaching a label to something that is unlabelable.

In fact, the word Sufi means one who wears wool, which I’m not doing now. And nobody would pride themselves of being called wooly. But it’s a word which was used, because in the early days the ascetics … you see the Sufis were essentially, were ascetics there’s no doubt about it. And they were poor, and in those days the sheik’s were … the Muslims were conquerors and they were rich. And now again, it’s happening again, they’re conquerors of the American capital, and they’re rich, too. And so, they were wearing cotton because that was much more expensive and therefore fashionable. Whereas wool, it was just too easy to find amongst the tribes in the desert. So wool was for the poor man. So the Sufis are the poor people who wear wool. And they were the fakirs, which means poor. And they were wearing the same garmment as the Christian monks in the desert. And in those days, all that the Muslims knew of the Christians were there were some monks in the desert who were living there, like Syriac monks who were living a simple life from the desert, and they were wearing wool. So, that’s how the word came.

I know that there are other interpretations of the word, like it might have come from Sofia, which means wisdom and, well it’s rather highfaluted interpretation, but it is true that at a certain … in the year 526, when Emperor Justinian closed the new neo-Platonic school, and it’s true that, from in Greece you see, it’s true that that Damaceus and his bretheren, who are of the Platonic … neo-Platonic school, or the continuation of Plato … Plotinus, sought refuge in Iran. And so it’s true that there’s Sofia of Greece was transmitted to Iran and there was a wonderful osmosis between Zoroastrianism and and the neo-Platonic school and it is possible the word Sofia, the Sufi came from that word, too, you see. It’s all very confusing.

And other etymology is also equally convincing, and that is that the Prophet Muhammad was receiving messages you see, which he took down … I mean, somebody took down. And they wrote it on, I think it was cowhide, and that was the Quran, you see. And he disclaimed that they were his words, they were words that were coming through while he was in a very high state. And there’s Zoroastrians in Iran who are very, had a very high culture and civilization as compared to the Arabs, heard about this prophet in the desert. So much success and such a following and a whole revival of spirituality in the desert.

And they sent a great Magi–Magus–and his name was Salman, Salman Farsi. Like the three wise men who visited Christ, you know that the tradition of the Iranian Magi were very formidable, men like kings and powerful. And so Salman Farsi was on his way to rejoining Mohammed in the desert. And in those days, of course, even nowadays of course, he was captured and made prisoner and then he was sold for … the tribe of the Prophet bought him as a slave in order to … by paying a ransom in order to get him to come. It was the only way.

And so there must have been a very deep link between Salman and Mohammed. And in the end, Salman initiated the Prophet Mohammed and his daughter Fatimah and his two sons, Hassan and Hussein– it’s called a mubahala–into what I believe was the Sufi tradition that was handed down from the Zorastrian Magi. And after this, then there was a group of people who met with, the intimate group was Hazrat Ali and Salman Farsi and, well I forget now some of the other names of people who were meeting on the … in the mosque of Medina … or, next to the mosque. Now next to the mosque, there was a place where they had these low cushions around which are called sofas. And they were called the al al-safa. That means the people of the sofa. So, as you see all of these words are perfectly plausible. We have the choice between which one appeals to us most.

There’s even another one. And that is saf, which means pure. And there’s a word, the word of a confraternaty of Sufis called al al-safa , which means “the people of purity,” “the knight of purity” … out of which came the word the “knight of purity,” in fact.

And as a matter of fact, there’s some–it’s, of course, a little bit complex– but there’s some etymology, etymological link between saf and pars, out of the words which comes Parsi, the Zorastrian Parsis. Saf means pure. And you can see it in the word Parcival, the name of Parcival, who is the master–Wali–of Saf, of purity. He’s the master of purity. The fact is, of course, the Grail legends have their origin in Sufism because, I don’t know whether you know this, but there have been studies, of course, on the legends of the Grail, at least the version of Christian and … who lived in the south of France in Provence, as they call it, which was a kingdom at that time. And it’s been shown that many of the terms used were … had Iranian origin. And the fact is that at the end of the Crusades there was a greater friendship between the Christians and Muslims. They had been fighting sometimes in a treacherous way, sometimes nobly.

Like there’s a case of, if I remember well it was Richard the Lionheart and, and … was it Salman? Salman I think … forget now the name not Salman the one I’m talking about … anyway, a Muslim knight. And Richard the Lionheart lost his sword and the Muslim knight stepped off his horse and picked up the sword and gave it back to him. So there were some demonstrations of and on the other hand of great nobility So they came to regard each other very honorably. And finally there was a truce. And the Muslims and Christians met in, yeah, a place which is still in the … next to the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, a big hall. And the password for meeting there was Fattah, which means “open the door.” There’s a password.

And it’s the same word that the knights used to use in order to pledge their allegiance to the sovereignty of the government of the world, spiritual government of the world. The same as were doing now in the Sufi Order. And it’s the same word that Christ used when healing a child who was born blind. He said Fattah, which means “open the door.” Now the legends of those (unknown), and meetings between Christians and Muslims were then carried through and presented from the Middle East, or the, well yes, the Middle East to Europe. The passage from the Middle East to Europe was through Sicily.

And in the 12th century, the king of Sicily was a German King. His name was Frederick the II of Hohenstaufen. He was a very wonderful initiate, a very high initiate, luminous being, very powerful, luminous and very Aryan, blonde. And he was also a great falconer and he had written a marvelous manual on falconry that has remained a classic throughout the centuries, and he lived in a castle. One of his castles was Castel Del Monte, in the south of Italy near the frontier of Sicily. And that’s where he welcomed these knights and troubadours who came from the holy land, who are telling these wonderful stories of great heroism and so on. It was like the court entertainment at the time and amongst them, they were court jesters. And there was I’m sure a lot of joy and laughter and wit and so on and wisdom sometimes behind that wit.

And this is how, as a matter of fact, the influence of Sufism spread in the South of France under the form of the Cathars. The Cathars were afterwards absolutely decimated by Philip the II, Phillip le Bel, with some connivance of the Vatican, because they were … believed in the unity of religions. And they were dedicated to service, they were healing the … healing and nursing the ill people, and they were absolutely dedicated people, wonderful people, the Cathars. They lived in caves in the south of France. And there was one time when the church came and with the help of the King of France and they killed them off like ….. That was the end of the Cathars influence.

So you see, Sufism had a lot of ramifications. And then of course, it also traveled along the path of the Muslim conquerors in Spain. And so there was a very strong influence of Sufism, in the development of mysticism in Spain, with Saint John of the Cross, and Saint Theresa of Avila. And Ramon Llull was a very good example. And Alcantara, again a mystic who spoke the language of the Sufis but a Christian mystic, but it’s as though you’re reading a Sufi book. And there was some live contacts between them. Ramon Llull was also an alchemist, and you know that alchemy was one of the strong aspects of the teaching of Sufism. That’s why we have the alchemical retreat, following up that same tradition.

The influence of Sufism probably reached Meister Eckhart. It’s very difficult to check on the dates of the visits of Meister Eckhart to Paris, how they synchronize with those of Ramon Llull, but it seems that at some time those two did meet. I’m giving you a little historical background behind it all. Now, the conquerors of India, the Muslim conquerors of India, amongst them were Sufis and mainly … the main one of the first ones was, Hujwiri. They call him Dātā Ganj.

And then later on, Khwājā Moinuddin Chishti, and that was in the … I suppose it was in the 13th century or 12th century … I think 13th (unclear). And he is the founder of the order to which we belong. I mean, of which we could be, we could say we’re “abzweigen” in Dutch and German, which means not just a branch, but a branch that has got a certain independence. In fact, that’s how the Sufis work. It’s not like a Vatican at all. It’s very centrally controlled, but a lot of ramifications. I came across in a library, in Hyderabad, I came across a manuscript that seems …. It’s likely that it is the words of Khwājā Moinuddin Chishti, but, one is always very, you know, there were many false documents in those days so one doesn’t … falsification, so one doesn’t know for sure. But the language is old Persian. But what I’m trying to say is that what he was … the substance of that book was that he was teaching the Zikr to Hindus. And explaining this, a little bit like what I was explaining this morning, like not just how to do the Zikr, but how that fits into the Hindu approach, which was, as I said, this morning, rather the opposite.

Well now, and what I would like to do is to present to you some of the Sufi mystics as persons but in view of, not just as persons who lived at a certain time and certain place, but for their contribution to our own experience, let’s say what they made an experiment in something that we are also experimenting, and how what they experienced can help us in understanding what is happening to us. That’s the only way in which it’s interesting to work with the old Sufis. Otherwise you can say, “Well, you know, that’s the past and why do we bother?” and so on.

Well, to start with, although now we are making … placing so much the accent on being in life, I do admit that the first Sufis, and even especially the first Sufis were extremely austere ascetics,

Abu’l-Khayr, for example, made a retreat of 40 years repeating the Zikr the whole day. Now I did it 40 days and I thought it was a lot and I keep on bragging of it. And Abu Yazid Bistami spent most of his life wandering in the desert with no shelter, and you know sometimes you can go a long time without finding water, get lost in the desert. And absolutely in the search of God … whole being like, you know, a kind of divine madness. And the same is true, Al-Hallaj also (unclear).

You see, what happens to … one has no idea what happens to a being when they dedicate themselves to such an extent to the search for God. The evidence of that is … a story that I often tell is that every now and again in India, an elephant goes mad. When the elephant goes mad, it kills its owner, it’s keeper. It breaks it’s chains, it rushes around in the streets and causes a stampede and crushes a lot of people. It breaks down houses. It becomes a monster, a dangerous monster. Nobody can control them. You know the strength of an elephant, there’s no way. And then they call the dervish. And the dervish doesn’t want to go … they collar him and take him …. And the dervish says, “Sit down.” And the elephant sits down. And everybody’s is just bewildered, wonder how on earth that dangerous elephant, he obeyed this dervish. And of course the reason is because the dervish thinks that he’s God, and the elephant believes it. It might make you laugh and it made me laugh the first time but I realized that in fact this is the essence of Sufism.

Remember the words of Murshid when he says, “the purpose of the message is the awakening of humanity to the Divinity in the human being.” That is, discovering the God in one. Just like Christ said, be perfect as your Father.

Now you could say well, couldn’t that not lead to megalomania? And Murshid answers that by saying, “the greatest pride together with the greatest humility,” or consciousness of the Divine Perfection, suffering from limitation in one’s being. And he calls it the aristocracy of the soul, together with the democracy of the ego. Reconciliation of the irreconcilables.

So there are times when the dervish falls back into his personal consciousness, and I suppose he is relatively humble. But when he’s in his divine consciousness, there’s no iota of humbleness there remaining. And, of course, you know, between you and me, of course, the reason why elephant and the dervish understand one another is the’re both as mad as each other. It’s a madness, as I say, it’s a kind of madness. It’s the … the ultimate wisdom is the ultimate madness.

The other thing about a dervish is that, he or she, because there are women dervishes, looks into your soul. And a lot of people are just afraid of the dervish because they feel exposed. They feel that they’re facing the light of truth. And the first thing that happens is one feels any guilt that one has. One feels it right away, comes up right away.

And the other thing is that, I suppose the dervish has gone through such personal sacrifice and such a stoic overcoming of himself that one just feels, not just guilt, one feels that one is lenient with oneself. Facing and therefore weak in comparison to the strength of the dervish, who’s not giving in to his whims. And it’s true that one says one likes the truth and so on, but when it comes to it, one doesn’t like the truth, it’s too harsh. And the other thing is the dervish becomes so powerful that he realizes that his being will shatter you.

Now, shattering is of course, one of the strongest terms used in Sufism, because … well, you … perhaps, you know those words of St. John of the Cross: “to become what you are you have to pass through a place where you are nothing.” And it’s true, and St. Francis said the same thing. And Christ said, “So that that the plant may be born should not the seed die?” and so on. So, it’s true that we have to go through a shattering. And the dervish enhances this shattering to such an extent that maybe one … it’s too much, maybe one isn’t ready for it. There’s a level, degree to which one can let oneself be shattered. And if it’s beyond that degree then perhaps one would go insane. One really needs to … there’s some … one needs to be protected. And the dervish knowing the shattering action of his presence upon you, will sometimes tell a person, “Don’t come near me, I’ll burn you. Don’t come near. And even keep really far away. Now of course the other reason is, of course, the dervish is very sensitive to, well, first of all to dishonesty. That’s the one thing that the dervish can’t stand is dishonesty. If he sees dishonesty in a person he feels like polluted so he doesn’t want to come near that person to get under that … in any way to receive anything of that shadow of that person … “keep away!” And some of the dervishes are really of course rather, I would say primitive, but that’s my judgment, and they throw stones at you if you come near them. You don’t know what hit you. I can tell you lots of stories of dervishes. You see, they will always tell you right on just exactly where you’re at.

Now, I can tell you a story of course, which I’ve told already more than once, when I was very young and I wanted to visit the dervishes in Karachi, and I was a guest of the Prime Minister of Pakistan. And his son was very interested in dervishes and Sufism and I asked … in fact, the Prime Minister was, too. And I asked him if he could take me to see a dervish and he said, “Oh, no, I couldn’t do that. But you know, if you go down this down this road and then the end, you cross over,” so and so forth. “And then there’s a market and there’s a old man in a blanket, sitting amongst banana peels and that’s him. He’s a great dervish.” So, I said, “Well, why can’t you take me? Are you busy? ” He said, “No, you see, I went to see that … I used to go and see that Dervish and one day he cursed me. And I was so shattered by his curse that I didn’t know what I was doing and I crossed the road and I had an accident and broke my leg.” And he went on to say, “As a matter of fact if I hadn’t broken my leg, I would have gone on this first flight of Pakistan Airways of which I’m the president, which crashed. So I said, “Well, if he saved your life by cursing you then, why don’t you let yourself be cursed again?” And he said, “Well, once was enough.”

So I went to see him. It was with trepidation. He was sitting on the blanket. Seemed a rather disagreeable man. And I was very young at the time. And I said to him, “How can one spread Sufism in the West?” I mean, if you go to see someone who you think has all the answers you’re going to ask him just the question that is most pertinent for you in your life, and that was the most pertinent question for me in my life at that time. And he said, “Never say anything if you think you can say it.” Now for me, who was brought up you know and … background of university, philosophy, and supposed to be able to express oneself, and to who was … whose whole life was expressing himself in words, tell you don’t say it if you think you can say it. And ever since I’ve always felt that I couldn’t say what I’m trying to say. It’s very, good for one’s ego.

Well, of course there are many stories of the dervishes.

The dervishes are very different from the rishis. While the rishis are sitting right up there in caves in the Himalayas, they found a good life, you know. There’s water and, well you know, if you know enough about herbs you can live in nature you can … roots you can stew and even without matches one can make some kind of a fire, a lighter with flints, and so on, you can really live on your own withoutthe need of anybody at all. They suffer from terrible hardships, like there are tigers and leopards and panthers, actually. Black panthers are very dangerous, and of course cobras.

I could tell you a lot of stories of …. A rishi who found this cave and then he … as he was lying down in the cave … no, he was sitting in the cave, that’s right, meditating, this enormous tiger came in because it was the tiger’s cave. It’s a very narrow corridor that leads into a kind of bigger recess at the back. I went into it. I had a terrible claustrophobia. It was very narrow. And so he had … there was a little light by his side. You could just see the face of this tiger, the eyes of the tiger advancing. And he said when theTiger … he waited until the last moment and the tiger was right in front of his lap, and then he gave him a real bang on his nose, and the tiger roared and backed out, and it’s very difficult for a tiger to back. That’s the last time the tiger visited that cave. But of course, he had to go out to to get water, and he was not on the best terms with that tiger.

Now, of course another story is this rishi who had decided that he was going to … he found this cave and you know they make a kind of promise that they’re going to spend 20 years or 10 years or whatever, sadhana in a certain place. That means they’re going to do these practices in a certain place. So he found this marvelous cave, a little bit sun, shade, water, everything. He thought, well, the one problem is of course if there are any tigers. And he thought, well, tigers well, they’ll … because the rishi has to take a bath every day in the morning. He thought well, they won’t be there in the middle of the day, tigers generally get to the water in the early morning, in the dawn. And they sleep in the middle of the day. So there he was, bathing in the water and there came this enoromous tiger. He got out of the water and he felt like running but to escape but he, for one thing he realized that it was the tiger would overtake him. and secondly he felt rather ashamed to run away, because after all he’s supposed to be a yogi master, and so he stood there trembling. And the tiger came, rushed to him and at the last minute the tiger slowed down, seeing him standing there so passively, and started licking his feet and then licking his hands and then purring like a big cat. And after that, every day when he took his bath the tiger would come and take a bath, too, (unclear). There are some wonderful stories of rishis living in those very dangerous circumstances and finding a way of being able to survive in the mountains.

The dervishes don’t have exactly the same problem because, well yes, there are some dangerous animals in the desert but not quite the same. There are snakes of course, but the dervishes very often they live in the nooks of … ruins of old castles, for example, or old walls of the town, places like that. That’s where you’ll find them. And so they’re much more, like much closer by. They’re much more In the urban areas instead of right up in the in the mountains. And that’s because, as I say, Sufism is much more like in life, than seeking samadhi beyond life.

Okay now, I’ll describe then each one of these Sufis, at least some of the Sufis.

I’ll start with Abu Yazid Bistami, who was an ascetic, probably a rather gigantic man who lived in the northern mountains of Iran. He went through different phases in his life. And the first phase was typical of what the Sufis … of the teaching of the Sufis. And that is, that the purpose of life is to become the expression of the divine qualities. Now, in our simplistic language one would have said, to become the instrument of manifesting the divine qualities. But in the Sufi view…. I will have to sometimes jump from one author to another or from one mystic to another. So, in the view of in Ibn Arabi, whom I shall describe later, that which manifests God is also God. God is not only that which is manifested, but that which manifests what is manifested. So, you can’t say you’re the … I’m the instrument through which God manifests. I am the divine manifestation, you see, because all is one so, I think of myself as an entity and not recognizing that everything is one which is the meaning of La ilaha illa ‘llah hu.

So in as much as we still have some vestige of our personal identity, then we say, may God manifest through me. And of course, there’s always an oscillation between that condition where one has lost one’s personal identity in the Totality, or where there is still some vestige of one’s personal consciousness. And when there is then of course, one says, may God manifest through me. And so his whole purpose in life was to become a perfect instrument through which the divine being may manifest on Earth.

And that’s the opposite of samadhi. It’s not seeking liberation in the samadhi state, moksha, liberation. No, it is the opposite. It is fulfilling one’s purpose on Earth. There’s a concern about what am I on Earth for? And it’s all based upon, let’s say, the very foundation of Sufi thinking, which is this hadith of Prophet Mohammed which I will now be quoting. I’ll come back to Bistami again because that’s the, how can i say, the pivot, the axis around which the whole of Sufism is built.

And that is, God speaking … these are the original words … you know, hadith means … while the Quran … Muhammad claims that the Quran was revealed to him while he was in a state of meditation and came through, hadith are things that he said. And people remembered them, they didn’t write them down. And I’m not quite sure, it may have taken eight years, I think before it was noted down on, I don’t know, some cow hides or something. So it’s the oral tradition, you see? So let’s say: they say that Muhammad said that, God speaking, He said, I was a hidden treasure, and I desired to be known, and therefore I created the world, because I desired to be known. Well, that is rather simplistic way of putting it, but still it says it.

So that would mean that the purpose of all of this was an act of self-discovery, whereby God discovered Himself. In order to discover Himself, he had to manifest potentialialities of His being. And we participate in that act in … every time that we come to greater realization, what we’re discovering is the being of God coming through us. Now, I’ll say right away, although there are many more things to say about this, the counterpart of this came from a dervish who was living in the desert of Egypt. He was called Abd al-Jabbar Niffari, who used to wander in the desert. A very mysterious being, and his daughter was married (unclear) family, and he used to come and visit his daughter’s family, and used to sit there and say rather fantastic, mysterious things that nobody could understand. And which fortunately his daughter took down. I don’t know how because, I don’t know they had shorthand in those days. Or, they certainly did not have dictaphones. And … but it’s amazing that … what came through is really amazing.

Now we read it today translated by Nicholson. It’s called ? Mawaqif. And it’s difficult if you make sense out of one sentence out of 20 pages, but that sense is already something, that’s really, that already says something. And then you may start familiarizing yourself more with that thought and then you discover something more. But it’s a way of thinking that is so challenging to our ordinary way of thinking. There’s no common denominator, so it’s very difficult to understand what on Earth he’s saying. But one of the more salient things that he said was, it was not in order to discover Himself, that He created you. It was out of love for you, that He descended from the Solitude of Unknowing. Now that … there’s very much in just that sentence, of course. But fundamentally, what it says is, the purpose of creation was love, instead of intellect, let’s put it that way, you see.

Descending from the solitude of unknowing is a … you know that word unknowing, you find it in that book called The Cloud of Unknowing. You see, according to the Sufis … right, I could really jump into this because … but I don’t want to confuse you too much. So I’ll try and be a little bit slow about it. But, see according to the Sufis, God has a knowledge of His being, let’s say in principio, as the Latin fathers used to say, in the principle of His being, which … and then there is a knowledge that is added to that, which comes by the manifestation of His potentialities in the form of the universe. So there are two forms of knowledge, a transcendent form of knowledge, which is called aqil, which means pure intelligence. And then a knowledge that comes by a feedback system, that which experiences in a feedback system, which is called Alim.

The first knowledge, which one might call transcendent knowledge, is the knowledge where intelligence knows itself. Everything is present within intelligence, without it having to project in a form, or in qualities or whatever, and dichotomize into consciousness and an object. Now, I don’t know whether you’re following me, but perhaps the clue to this is the word of Murshid Hazrat Inayat Khan when he says, intelligence becomes consciousness, when it is faced with an object. And when you void your consciousness of any object –and that’s what Yoga is about– then consciousness cannot stand by itself without an object. And therefore it returns into its foundation which is intelligence. I don’t know whether this is clear to you, but …. Murshid says, the object limits consciousness.

Or, you could say that consciousness … well, Buddha, Buddha said it very clearly he said, consciousness is like a flame. And it can only survive so long so there’s something to consume. So as long as consciousness is being conscious of objects, it can survive. But if you void it of any kind of perception of the outer world if you sat in a Lilly tank, for example, and then you do some yoga practices where you emptied your mind of any thoughts or images, and so on so that there was … and emotion. So there was no content of consciousness. It would just return into its ground, which is pure intelligence. And that is what happens in deep sleep. Because in deep sleep, in sleep with dreams, there are objects and thoughts and emotions and so on. So consciousness is still active. But in deep sleep, there’s no more, there are no more objects. There’s no more experience. And that’s what scientists at least infer from the fact that there is no more rapid eye movement, as you know. And all that remains then is pure intelligence. There’s no more consciousness. And that is samadhi, is where there’s no more consciousness, it’s just pure intelligence. So that would be like the state of God…. Now, the word used by the Sufi is azalliyat, which means prior to existence. But that’s a mistaken concept, as one could say, it is the state of God beyond existence, maybe you could say, but not prior to existence. So that state can still subside while there’s another state that is added to it and that is a state of God in existence. It’s like you could have an eternal … eternity parallel with transiency so that as Thomas of Aquinas said, God is static and dynamic at the same time. So one aspect of God is in the process of becoming while, another aspect remain static. And what one is experiencing … experiencing is not the right word, but there’s no other way of saying it, is the state of God static where there is no transformation, no becoming, there’s no, birth no death and so on so forth. Just like a pendulum. The point of where the pendulum is suspended does not displace itself. It’s the only point that doesn’t displace itself. The other end of the pendulum is moving. I might add to that something that is a little bit more difficult to understand. And that is that there’s a point when the pendulum has attained the end of its swing, where it is suspended in time, where time is suspended. And that’s the way how eternity can be, can be incorporated into the process of becoming. And that’s why we sometimes experience eternal moments right in the middle of our daily life when we’re caught up in the process of becoming. So you see there’s a lot in that word, in that very little sentence of Niffari, but very significant sentence, where Niffari says God descends from the solitude of unknowing. And when he uses that word unknowing he’s used the word Alim, which means where there is no Alim yet, no kind of feedback … knowledge … there’s a feedback system as you know. We pick up information from the environment. We pick up information about ourselves by the way the environment reacts to ourselves and so on so it’s … that’s the kind … what they call speculative knowledge.

Now that word solitude is very important, because for the sufis, in His outbreath God descends from the solitude, of oneness into multiplicity and in this in-breath, God throws all things back into Unity again. And so, there are moments when we experience the need to fulfill the purpose of life, which is making God a reality in our being. Then we are sharing the divine outbreath. There are moments when we feel a need to retire from activity. And we go on retreat, for example. Or we have a need for peace instead of joy. Or then, we experience resurrection right now, which is one of the maxims of the Sufis: die before death and resurrect now. That means you already now you go through a process of disintegration. And already now you experience what it’s like to resurrect in anticipation for what will happen after death–after the death of the physical body. Prepare yourself for death. And that’s one of the things which people are now beginning to work with dying, death and dying. Because people used to ignore it before; now one realizes it’s this very real thing. And that if one is not prepared for it, one goes through a lot of trauma. That’s why the Tibetans have the Tibetan Book of the Dead. And the Sufis have a whole teaching about resurrection. How one works with preparing the body of resurrection. And the way to do it is to identify yourself with the essence of your being. There’s a shift of identity, so that you think of yourself as pure spirit. Well, we’ll be going into that a little later, although there’s so many ramifications as soon as you speak of any subject about Sufism.

So to come back again to Abu Yazid Bistami. In the first phase of his life, he felt a need to fulfill the purpose of life, and to become then the expression of the Divine bounty, that is the divine treasure that desired to be known.

I’m going to have to explain this a little more. Because Sufism is so subtle, there’s so much, really see the detail of what is very precise. You see, you’ve noticed in this hadith two things: I created and I desired to be known. One could say, the object created the subject that knows. Now, every sufi … no, quite a number of Sufis have made commentaries on this hadith of the Prophet. And my commentary is, instead of I was a hidden treasure, I would say I was a latent, many-splendored bounty. And instead of saying, and I desired to be known, I desired to manifest as a reality, and thus discover those potentialities.

And one could even say, and I desired that as I manifested, each fragment of my being should share in my discovery of myself. And therefore, I became in every human being or every feature, the object … the subject of my self-knowledge. Or one could say, and I dichotomized into a consciousness and a nature, and therefore I became in the consciousness of every being the subject of my self-discovery. And I became in the personality of each being the object of my self-discovery.

So in the beginning, there’s this knowledge without dichotomy between subject and object–it’s all one, total knowledge of pure intelligence. And then there’s a second form of knowledge that is added. And where there’s a dichotomy between subject and object, and where there’s a multiplication of subjects and objects, although apparent but basically, it’s all one. And the best example of that would be like the cells of the human body. Within the cell of each body there is the code of the … between each cell of our body … within each cell of our body, there is the code of the whole body. And so, as this bounty proliferated, each fragment carried within it the nature of the totality, and carried within it the consciousness of the totality. Now, I’m going to go one stage further and then we have our break because I know this gets pretty much into a mind trip, and requires a lot of concentration. Remember that Sufism has been called the metaphysics of ecstasy. It’s not just a mind trip, but the subtlety of the thinking forces us beyond our usual thinking. And every time that one is free from a limited vantage point one experiences ecstasy.

Well, I would say the most brilliant of all the metaphysicians in Sufism was Ibn Arabi, who was born in Murcia in Spain, and who is still unsurpassed in his … in the subtlety of his thinking, and the clarity of thinking.

So if you follow me now, I would say: by looking upon myself as an extension of the divine consciousness I confer upon God a further mode of knowledge. If you like, I help Him in His self-discovery. And by manifesting Him in my nature I confer upon him a mode of being. And I can go further than that and say: by … well, thinking of my consciousness as being an extension of His consciousness I do confer upon Him a mode of being by realizing Him in my being. And by manifesting Him In my nature I do confer upon Him a mode of knowledge because he’s able to discover Himself in my nature. So those are the four propositions.

So that the responsibility is somehow delegated down, so that although it is God who is experiencing Himself and discovering Himself, there is some participatory action of the human being, who nevertheless is part of the Divine Being but still there’s some relative autonomy there. So there’s some contribution that we make by our will, to the divine self-discovery. And therefore, because if He has granted to us His being, he also grants to us His will, and herefore His will is delegated further and further. And so, seen from the human point of view, it is our purpose to manifest God, and therefore help him to discover Himself, but only inasmuch as we manifest His perfection. And the point is that we are always standing in the way, or let’s say obstructing this self-discovery of God by looking at things from our vantage point, and forgetting that our vantage point is only a contribution to the total vantage point. And by being caught up in our own personality, instead of realizing that our personality is an expression of the divine nature.

So that was the first phase of Abu Yazid Bistami’s experience. And I think we need to have a break at this moment. It’s so very concentrated, requires a lot of attention on your part, and the sun is shining outside so why not just go and have a break of, let’s not make it too long. Let’s say, quarter of an hour and then we’ll continue.